Rewind to the early hours of January 17th, 1991, in dark Middle Eastern skies.

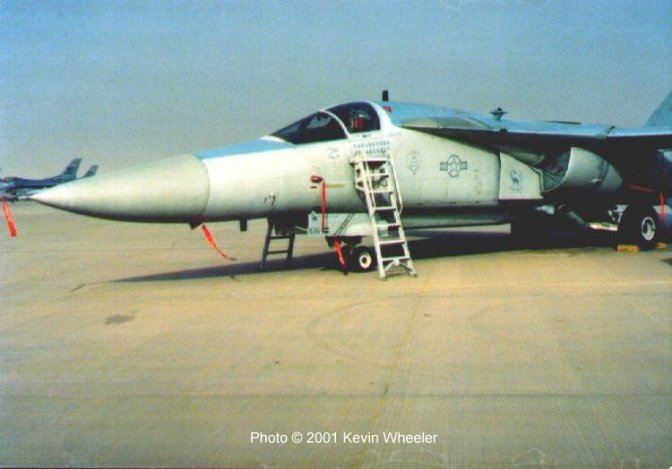

You’re flying in a two-seater General Dynamics EF-111 Raven, a heavily modified F-111 Aardvark strike swing-wing bomber. However, unlike the Aardvark, your Raven doesn’t actually possess any attack or strike capabilities. All the freed-up space is crammed with complex electronic warfare gear, designed to fool and jam the search and tracking radars of enemy missile stations. This makes your jet an extremely important asset to battlefield commanders, but also, a very high-priority target for enemy fighters. Miles away at Iraqi airbases and airfields, Mirage and MiG air defense fighters sit ready on the tarmac, armed and fueled up for the inevitable scramble order that will pit them against the incoming Coalition strike force. A number of Iraqi fighters are already airborne, lurking around, scanning for targets of opportunity. Your Raven comes standard with a limited load of chaff and flares, designed to confuse radar-guided and heat-seeking missiles. You can only pop flares and dump chaff so many times until you run out and all that’s left is high-G evasive flying or the striped ejection handles ominously yet reassuringly present in the side-by-side cockpit. Such was the situation Captains James Denton and Brent “Brandini” Brandon found themselves in on that fateful morning as they flew ahead of the opening aerial campaign of the Persian Gulf War. Though they didn’t know it just yet, they were in for a heck of a fight that would mark their names in the aviation history books next to one of the weirdest accomplishments ever credited to military aircrews in modern air combat.

Denton and Brandini, pilot and EWO (electronic warfare officer) respectively, were given the vital task of leading in the Coalition attack flight during the opening hours of the Persian Gulf War. Their mission was to protect the flight from Soviet-export surface-to-air missile emplacements, littered across the terrain below, courtesy of your friendly neighborhood Iraqi military. They flew with the knowledge that they would have fighters, namely F-15 Eagles and F-16 Fighting Falcons, functioning as a “screen” against marauding enemy jets that sought their fiery demise. After entering contested airspace, Denton reduced their Raven’s altitude to a little over 1000 feet, skimming the treeless Middle Eastern desert floor, while Brandon monitored the electronic warfare gear packed into the sleek jet. The group of aircraft they were guarding flew onwards, unable to be tracked and thus engaged by the SAMs below, thanks to the Raven’s efforts. Meanwhile, a USAF F-15C pilot got his eyes on an Iraqi Mirage F1EQ supersonic fighter. He quickly engaged the bogey, giving chase as the Iraqi pilot noticed someone was on his tail and actively trying to mail a missile his way. After twisting and turning, he popped flares and banked away hard, causing the Eagle pilot to lose sight of his quarry for a split second. It was enough to give the Mirage pilot a bit of distance so that he could retreat from the fight. Within moments, his eyes latched onto the low-flying Raven and he turned his nose towards it, throttling up as he tore through the sky to attempt a missile kill of his own.

Completely unaware of the Iraqi F1EQ coming towards them, Denton and Brandini were taken by surprise when the instrumentation in their cockpit lit up and started blaring. They were being painted. Their training immediately kicked in, and Denton went evasive. Right at that very second, the Mirage let loose one of two R.550 Magic air-to-air missiles it was carrying, right at the hapless Raven. While Denton focused on twisting the Raven away from its original flight path, Brandon smoothly operated the countermeasures console, popping flares. The combination of the hard maneuvering and the flares managed to do the trick, and missile, an IR-guided heat-seaker, swerved away, missing the Raven. Undeterred and somewhat annoyed, the Iraqi pilot carried on with his pursuit.

Quickly, once again, he had the unarmed Raven in his HUD. The Mirage shuddered as another Magic AAM left the rails and streaked towards the Raven. Denton was forced to put the Raven into another evasive maneuver, slamming him and Brandon back into their seats, while Brandon released another salvo of flares. It worked. The missile was fooled away from the fleeing Raven. Though the Mirage had exhausted its external stores, they weren’t exactly out of the woods just yet. During the constant stream of radio chatter, word came over from another F-15 pilot who was rapidly closing in for a long-range missile kill on the Mirage. The tell-tale screech of a radar lock began pounding the Iraqi pilot’s eardrums while he flew after the defenseless Raven, now attempting a guns kill on Denton and Brandon. If they didn’t do something fast, they were going to be the recipients of a bunch of 30mm shells, spat out by the twin DEFA cannons of the Mirage.

Denton came up with a plan on the fly, no pun intended. He would bring the Raven extremely low to the ground, and would navigate the dark, low-visibility battlespace using the Terrain Following Radar built into the jet. Easing the stick forward and reducing power, Denton brought the jet closer to the desert floor, and just as they expected, the pursuing Mirage came right with them. Zipping along, swiftly dodging dunes and the general geography of the terrain below with Brandon’s instructions (he was paying attention to the TFR while Denton flew), Denton suddenly yanked on the stick, pulling it back into his chest while simultaneously ramming the throttles forward. This threw the EF-111 into a climb, its powerful Pratt & Whitney TF30 turbofans pushing it to the speed of sound in seconds. This signaled the end of the Mirage pilot’s luck. The deadly mixture of target-fixation and a brief loss of situational awareness, thanks to the darkness outside and the low altitude, proved to be his undoing. He flew hard into the desert, obliterating his aircraft into bits and pieces with the fireball blossoming forward, right underneath Denton and Brandon. The two breathed a sigh of relief. They had somehow just scored the first ever F-111/FB-111/EF-111 air to air kill in its entire service history, and without even firing a shot (not that they could anyways). Their actions and superior airmanship earned both the Distinguished Flying Cross, with numerous witnesses attesting to their bravery and skill as they saw it that January morning.

The EF-111 Raven remained vital to the aerial component of the Gulf War in that day, and every day beyond that it took to the skies. US Air Force Ravens were so successful at keeping surface-to-air missiles at bay, that whenever one was on station during the Gulf War, and subsequently, Operation Southern Watch, absolutely no Coalition aircraft were ever engaged and lost due to SAM action.

On almost all digital SLR’s, the memory media will be SD card.

If truth be told some great benefits of having an affordable virtual

digital camera are many. If you absolutely must check your equipment in because

it is just too much stuff to carry with you,

there are a few things you can do to ensure it gets to

your destination safe and sound.

LikeLike

One of the many great feats that this weapon system could do. It was an engineering design to build the future AF aircraft, too bad it does not get the recognition it deserves.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Almost nobody knows of the fierce tiger-like battle the original HQ/TAC EF- 111 project officer had to win vs. the HQ/TAC fighter pilot mafia in the early 1970’sto win to keep the TFR and remove the gun from this bird

LikeLike

I worked at Grumman Aerospace in 1976 when I was assigned to this flying disaster. The aircraft were old. We had crappy copies of drawings and even worse microfiche. Our leader, a future “bright boy”, had his career ruined there. We had effectivity problems, is this A/C 452 or 529? There were undocumented field expedient repairs, this part has either four holes or five. It had seven. I have 34 years experience in aerospace mainly in Structural Design. This program was the worse one I ever worked on.

LikeLike

First off I served in the 77 TFS 1980-1987 with the F-111 being my first assignment. That said. This story has a life of its own. I myself believed this to be true. The claim was written in a history pamphlet on 20th Fighter Wing by its historian in 1994 and again in a history booklet by the 20th Fighter Wing Association (1995) and by myself in an update to the Associations booklet in 2007. It was not until I took on the job as the 20th Fighter Wing’s Historian at Shaw AFB in 2008 that I tracked down what actually happened. I know at the time all at Taif AB, Saudi Arabia believed that this was “Officially the first kill.” But the final determination would not have been determined there. The initial claim would have been made at Taif but later all claims were reviewed looking at all data (including AWACS tapes) to determine the validity of the claims after which a final list would be compiled and orders (not medals that is a separate process) would be issued for said claims. As the historian for the 20th Fighter Wing Association I have many pilot encounter reports from WW II that made aerial victory claims that were approved at Squadron level, 20th Fighter Group level, 67th Fighter Wing level (what we now would call an Air Division) and 8th Air Force level that were later disapproved at what became USAF level. The official award for the F-1 Mirage kill went to Capt Robert E. Graeter, 33 TFW, Special order CCAF SO GA-1, 1991, as a Maneuvering kill. You can check with AFHRA, http://www.afhra.af.mil/ and ask for the list of aerial victories for Operation DESERT STORM. AFHRA is working on putting all victory claims up on their web site in the near future, but until that time you can request the information directly from them. Not looking to pick a fight but as historians we have to try (and often fail) to keep the record as accurate as possible. The web with sites like Wikipedia and others have made this task even more challenging because information on the web stays forever and just when you think you’ve settled something someone else cuts and pasts something to another site. None of this detracts from the actions of EF-111’s crew in evading the attack by the F-1. We’ll never know if the F-1 would have crashed anyway even if the F-15 was not engaging.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey Art, thanks for the insight! If at all possible, I’d definitely love to discuss this in detail with you! If you could shoot me an email sometime via the contact form on the website, I’ll respond right away and we can hopefully set up a brief conversation!

LikeLike

It is true, I was one of the Crew Chiefs assigned to that aircraft with the 42nd ECS out of Upper Heyford

LikeLike