By Tom Demerly for ALERT 5.

It flew at nearly Mach 7, seven times the speed of sound and twice the speed of a rifle bullet. The speed record it set 47 years ago today still stands today.

It flew so high its pilots earned Air Force astronaut wings: 280,500 feet or 53.1 miles above the earth.

It pioneered technologies that were used on the SR-71 Blackbird, the space shuttle and the reusable spacecraft in Richard Branson’s future Virgin Galactic passenger space program.

And it killed test pilots in an era before redundant flight control systems and modern safety protocols for hypersonic flight.

It was the North American X-15. Today is the 47th anniversary of its fastest ever manned, powered flight.

The X-15 could be the most ambitious and successful flight test program in aviation history. Apollo astronauts flew it. It challenged the paradigms of aerospace design well beyond the limits of any prior program, including Chuck Yeager’s sound barrier busting Bell X-1. The X-15 program sits alongside the Wright Flyer as an aviation milestone. So much progress was made so quickly in the face of such great risk with such rudimentary technology that no other development program, with the exception of the Apollo missions, has come close.

10:30 Hr.s Local, Tuesday, 3 October, 1967. Edwards Air Force Base, Mojave Desert, California.

After the awkward and tedious process of donning his pressure suit, Air Force test pilot William J. “Pete” Knight, clambers up a custom made ladder and lowers himself into the cramped cockpit of X-15A-2 aircraft number 56-6671. Half a dozen men helped Knight get ready for his flight this morning, testing life support equipment and helping him into his bulky pressure suit. His first astronaut type flight helmet attached to his pressure suit didn’t work with his aircraft communications system, so technicians have replaced it with a backup pressure suit helmet. Communication checks are normal now.

The X-15A-2 rocket plane is mounted between the number 5 engine and the fuselage under the right wing of “Balls 8”, a massive Boeing NB-52B mothership. Today it’s flown by Air Force Col. Joe Cotton and Lt. Colonel Bill Reschke Jr. The launch aircraft has a sprawling 185-foot wingspan and eight jet engines. It was originally a B-52 strategic bomber built for dropping hydrogen bombs on the Soviet Union if the Cold War ever got hot. The bizarre pairing of aircraft, the little X-15 nestled under the right wing of the giant silver and red B-52, is parked at the beginning of runway 04R/22L, a 3 mile long × 300 foot wide strip of reinforced concrete with an additional unpaved 2 miles for emergencies. Other than the sounds of vehicles coming and going it is quiet and still at Edwards Air Force Base in the wide expanse of the Mojave Desert.

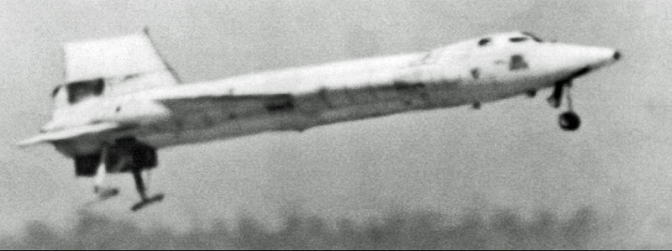

This X-15 is different than the only other two aircraft of the same type. The other two X-15’s are painted black and have a yellow NASA band on their vertical stabilizer with U.S. Air Force markings on the fuselage and wings.

The X-15 Pete Knight is strapping himself into is an “X-15A-2”. It has no exterior markings. It is covered with a milky white ablative coating to resist heat and carries a pair of giant anhydrous ammonia tanks under its fuselage. The rocket plane is made of a special, ultra strong alloy called “Inconel-X”. As Inconel-X heats up it actually becomes stronger. The X-15A-2 burns a volatile mixture of deadly ammonia and liquid oxygen as fuel. When ignited, its single XLR99 engine burns 7 tons of fuel in just over a minute and generates half a million horsepower, nearly 60,000 pounds of thrust. By comparison a modern day F-16 fighter generates about 30,000 pounds of thrust in full afterburner.

Today’s flight profile has one objective: speed. It is an attempt to set a maximum manned-flight speed record. The X-15 will be a piloted projectile blasting through a violent acceleration from 500 MPH to nearly 5,000 MPH in only 75 seconds. Six times the speed of sound. On the downside of this flight profile the X-15A-2 will decelerate so violently that a rearward-facing crash pad is installed in the canopy, in front of the pilot, so Pete Knight’s helmet can slam into something soft as the friction of the atmosphere slows the plane after its explosive fuel burns out.

Test pilot Pete Knight is hot inside the X-15A-2 cockpit. The desert sun in the Mojave is unrelenting. The cockpit is pressurized with nitrogen gas and Knight is breathing oxygen fed to him through his spacesuit. In an emergency Knight needs to get the X-15A-2 below mach 4 and 120,000 feet to use his rudimentary ejector seat to escape. His chances of surviving an ejection in that corner of the performance envelope are slim. Outside that envelope, where the X-15A-2 will fly today, they are zero.

A little over a month later, on November 15, 1967, USAF test pilot, Major Michael J. Adams will die when his X-15 enters a violent spin at mach 5 and disintegrates under crushing G-loads. Wreckage is strewn over 60 miles and two states. He is remembered as the first fatality of the U.S. space program.

Knight communicates with ground control and the crew of his NB-52B mothership over his radio as he prepares for his record setting mission. Checklists are read and verified, engines on the NB-52B are started and the aircraft taxis heavily onto the long runway with a following group of crash, fire and support trucks trailing behind. Two chase planes, a “Century Series” F-104 Starfighter and an F-100 Super Saber, prepare to take off to follow and observe the mission until separation. A second set of chase aircraft will be in the air to receive the X-15A-2 as it decelerates back toward Edwards for landing at the end of the flight. Two sets of chase aircraft are needed, one pair at the start of the flight and one at the end. Nothing in the air can follow the X-15A-2 through its flight, not even a missile. Nothing is fast enough.

The sky is brilliantly clear, arcing dark blue up into a vaulting space that seems to dare the test pilot strapped into the milk white missile-plane. It is a deadly empty space where physics are a cruel arbiter. The “surly bonds of earth” are comfortable and safe by comparison. The vast test range where the mission is being flown covers three states, Utah, Nevada and California. Knight will hurtle across these states in a blur only seconds long covering well over a mile per second.

The take-off roll is long and oddly slow looking. The NB-52B wallows into the air with an unusual flight attitude, black smoke settling rearward from its screaming engines. Knight is a passenger inside the X-15A-2 for the moment, calmly reviewing procedures and checklists and re-checking his flight profile and navigational range card strapped to the right leg of his spacesuit. It is about 13:40 local time.

The climb to launch altitude takes time. Chase aircraft close in on the NB-52B/X-15A-2 pairing in preparation to conduct visual checks of flight control actuations prior to launch. A local NOTAM, or Notice to Airmen restricts all civilian air traffic from the area.

The white X-15A-2 is not as attractive as its black predecessors. It looks almost like a mock-up, not a real aircraft, since the paint appears blotchy and hastily applied. The giant ammonia tanks look like an afterthought strapped to the pasty missile-plane. Despite all the planning, training and preparation the X-15A-2 looks more like something preparing for a crash test than the threshold of a new aviation speed record.

Even with meticulous preparation, planning and checks the X-15 missions were often filled with unexpected incidents. On an earlier flight, test pilot Scott Crossfield’s X-15 cockpit filled with smoke while it was still mated to the NB-52A. Almost immediately after radioing the crew inside the NB-52A mother ship about the smoke in his cockpit, Crossfield’s radio in the X-15 went dead. The implication of a burning X-15 filled with highly explosive ammonia and liquid oxygen attached to the wing of a B-52 caused the crew to consider dropping the X-15, not knowing if Crossfield was still alive or already incinerated in a deadly cockpit fire that would touch off a massive explosion any second. Crossfield told the NB-52A crew earlier, if there was any question, “Drop me”, since “There is one of me, and four of you.” Oddly, the smoke in Crossfield’s cockpit cleared and the radio began functioning again. The mission proceeded as normal.

The central risk of the X-15 concept, especially when it was chasing altitude records, was that it crossed from atmospheric flight to non-atmospheric near space flight. Those two regimes are vastly different. One has air, the other doesn’t. In the atmosphere aircraft steer by using control surfaces over which air moves. Move part of the flight control surface as air is moving over it, and the plane moves. In near-space the rules change entirely. There is, effectively, no atmosphere or air moving over flight control surfaces. The aircraft uses miniature rockets mounted in the nose and tail to control its yaw, pitch and roll. In 1967, it was an imprecise science. In the atmosphere the stubby wings and small control surfaces of the X-15 had little purchase. In near space they had none.

Once at drop altitude of 45,000 feet final checklists and systems checks were completed. There was a countdown. The X-15 was released at precisely 14:31:50.9 local time. It dropped at a slight angle from under the wing of the NB-52A, quickly rolled level, dropped further then ignited its engine.

A brilliant white contrail lanced forward of the lumbering NB-52A and the supersonic chase planes struggled to try to keep pace with the X-15. They were quickly left behind. The white trail traced a curve upward, upward, vaulting away into the western sky. Blue sky gave way to black. And there was a concussive explosion.

The sound barrier is broken when a succession of shockwaves accumulate on the nose of a projectile. Or aircraft. When they are compressed enough, the explosion happens. Like the crack of a bullet. There are often two sonic booms. In this case, there is no record. But over the next 75 seconds Pete Knight accelerates past the sound barrier- and keeps on accelerating. Mach 2…3…4… There is no secondary sonic boom as Mach speed accumulates. No dramatic acknowledgement of a new speed frontier being crossed.

Mach 5.

Five tons of anhydrous ammonia and liquid oxygen have burned in a barely controlled explosion 15 feet behind Knight’s ejector seat. Two tons remain.

Mach 5.5.

A by-product of speed in the atmosphere is friction, and a by-product of friction is heat. Pete Knight’s X-15A-2 begins to melt. The leading edge of the wings glow at over a thousand degrees. Even at high altitude the air molecules can’t get out of the way fast enough to dissipate heat. So chunks of Knight’s X-15 begin to burn and fall off. Big chunks. During flight, shock waves burn through the leading edge of the lower ventral fin igniting a series of small fires in the engine housing. Near the explosive nitrogen tanks.

Mach 6.

Knight already has the throttle advanced to the forward stop. One of two things will happen; he will complete his fuel burn and set a new speed record by a massive margin…

He passes through Mach 6.5.

Or, he will disintegrate as the accumulation of heat causes a massive structural failure of his airframe that will result in an instantaneous explosion of any unburned fuel. It’s unlikely much wreckage will be found.

Mach 6.6.

A big part of the X-15A-2’s ventral fin ignites and burns completely through. It flies off the aircraft, tracing a bright, burning arc to the desert floor.

Mach 6.7.

Fuel burn complete. Flight profile nominal. Powered flight terminated, ballistic flight initiated. Knight is still alive and at the controls of the world’s fastest glider. The X-15A-2 had reached its maximum velocity, a new manned flight speed record by a huge margin. It arcs over the Nevada-California border, over a mile a second, leading edges still glowing from heat. Accumulated heat detonates the separation charges on the dummy scramjet carried for test purposes. It explodes away from the X-15A-2 over Edwards bombing range as Knight decelerates through Mach 1 and 32,000 feet, more charred junk toppling to earth. Knight continues to descend, burning fragments dropping off the aircraft as he flies. The relentless forces of physics reel in ambition once again. But only after history is made.

Somewhere east of Edwards Air Force Base the second set of recovery chase aircraft find Knight as he descends and decelerates to enter the landing profile. The X-15A-2 is charred. There are visible holes burned through the ventral tail. Would the landing gear still function? Had the single nose wheel tire melted from the heat? The rear landing gear on the X-15 was a pair of stubby, ski-like skids designed for one-time use.

Knight extends his nose wheel, landing skids, speed brakes and sets flaps for landing. A chase pilot confirms that the landing gear appear intact. He touches down at 14:40:07 local time on Rogers Dry Lakebed runway 17/35. A billowing plume of dust erupts behind his two rear skids as the X-15A-2 slides to a stop on the 7.5-mile long runway. The flight lasted 8 minutes and 16 seconds and covered over 213 miles of the western United States. Knight’s rocket engine only burned for a fraction more than 2 minutes and 20 seconds of the flight.

William J. “Pete” Knight’s speed record remained unbroken by any winged craft until the space shuttle Columbia’s reentry from space on April 14, 1981. His speed record still remains intact for a non-orbital aircraft.

Pete Knight had become the fastest pilot to fly inside the atmosphere in powered, controlled flight. A record that officially remains today.

The massive achievement of the X-15 program, both speed and altitude records, would pave the way to the moon and the space shuttle program. Its technology dividend is truly immeasurable, touching everything from the GPS constellation to cell phone communications and even the idea of civilian space travel.

Knight was awarded the Harmon International Aviator’s Trophy in 1969 for his record setting flight by then-President Lyndon Johnson. Following his test flight program in 1968 Bill Knight transferred to an active combat unit and flew 253 combat missions over Vietnam in the supersonic F-100 Super Sabre. For Knight, flying the Super Sabre after the X-15 must have felt like going from a dragster to a dump truck.

Pete Knight left the Air Force and began a political career in 1984. He eventually became the first ever elected Mayor of Palmdale, California. Under Knight’s term Palmdale was the fastest growing city in the United States. He was later elected as a Republican Senator for the 17th District of California.

In an odd footnote Knight wrote legislation in California called “Proposition 22” that banned same-sex marriage. But one of Knight’s sons, David, was gay. David Knight defied his father and married his same-sex partner during a loophole period of the law in San Francisco. Proposition 22 was later repealed in California after being judged unconstitutional.

Air Force Test Pilot, speed record holder and decorated combat fighter pilot William J. Knight died in 2004 at the age of 74. His manned, atmospheric speed record still stands. That we know of.

The actual X-15A-2 flown by Knight was restored after the flight and returned to the original black paint scheme but never flown again. It is now an artifact in the Air Force Museum at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio.

Not sure what Proposition 22 has to do with this article. It really takes away from the story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Definitely has 2 nose wheels in the pictures.

LikeLike

“…sits along side the Wright Flyer as an aviation milestone”

This experiment was 47 years ago, and Chuck Yeager’s sound barrier flight was in 1947, yet they try to minimize it by comparing their experiment to the very first successful aeroplane flight that had NO deaths with the model that was used. Jealousy?

LikeLike

Nitrogen is not explosive.

LikeLike

Why bring up Prop 22? It has no bearing and adds nothing to this Hero’s service to our country!

LikeLiked by 1 person

THIS EVENT MARK ONE ICON IN MILITARY-AVIATION.

LikeLike

I got to know Senator Knight when I worked at the Capitol in Sacramento. The nicest, most humble man ever. I had heard about his flight record but I did not know about all those combat missions in Vietnam. A true hero and patriot.

LikeLike

It is true jackie

LikeLike

Right you are Ray, Nitrogen is NOT explosive, however, the tanks are pressurized, and if ruptured, can explode!

LikeLike

George Welch was the first to exceed the speed of sound. Two weeks prior to Yeager’s flight Welch, a North American test pilot, exceeded the speed of sound in an F-86. Sonic booms were heard over Muroc that morning.

LikeLike

Buy game accounts cheap

LikeLike