The early weeks of April, 1975 found the USS Midway steaming towards the coast of South Vietnam to link up with a number of other warships including the USS Coral Sea and the USS Enterprise of Task Force 76, standing by to support Operation Frequent Wind, a mass evacuation of all American nationals and as many South Vietnamese military personnel (and their families) as possible during the North Vietnamese Army’s final push into the South. Reaching its station on the 19th, the Midway had previously offloaded half of its air wing at Subic Bay on its way to Vietnam and her sailors were prepping to receive thousands of evacuees in the coming days. To assist with the evacuation, ten massive US Air Force Sikorsky HH-53C Super Jolly Green Giants were loaded onto the Midway while at Subic. On the 29th, orders were handed down from higher- Operation Frequent Wind was a go. It was on that very day that Major Buang Lee (also spelled as Buang-Ly in a number of other accounts) of the South Vietnamese Air Force unintentionally had his name etched into the record books by attempting and completing one of the weirdest carrier landings in history aboard Chambers’ ship.

By the end of the war in Vietnam, a fairly sizable number of Republic of Vietnam Military Forces (the South) officers and senior enlisted soldiers/airmen, as well as their families, were marked for death. Their civilian peers in the South were especially fearful of reprisal from the invading North Vietnamese Army for supporting and harboring ranking RVNMF personnel, who were often unceremoniously dragged out from their houses and shot in the streets, their bodies left to rot as both a warning to anyone who wouldn’t give up RVNMF troops and to the soldiers themselves that their demise was imminent. Anyone who was seen or thought to have aided the United States in any way, shape or form, was hunted down and mercilessly slaughtered. The US military offered a way, during Frequent Wind, for these men and their families to flee to safety. Their places of refuge were the decks of US Navy vessels floating off the coast of Vietnam.

Major Buang Lee, a young officer with the Vietnam Air Force, was extremely worried for the safety of his wife and five children. If Northern soldiers came across them, or their neighbors gave them up, torture and execution was the brutal fate that awaited them. Unwilling to let this happen, he crammed all of them into a small Cessna O-1 Bird Dog parked on an airfield ramp on Con Son Island and took off. The Bird Dog was the military version of the Cessna 170 and it generally flew with two crew- a pilot and an observer; Lee’s Bird Dog was packed with seven people, including the pilot. After lifting off from Con Son, the Bird Dog took fire but was miraculously left unscathed. The plan was to fly out and hopefully find an American warship, ditch the aircraft and swim to safety. If they couldn’t find a ship, they wouldn’t have any other option than to ditch anyways. Luckily, the Lee family spotted a cluster of vessels in the distance, and twisted the aircraft in that direction.

Aboard the Midway, Frequent Wind was winding down. South Vietnamese and American UH-1 Hueys, previously hauling over evacuees, were chained to the flight deck while crew moved to-and-fro in the light rain soaking the carrier. The bridge of the Midway received reports of an approaching small aircraft, though they were unable to determine its origin and intentions. Observers with powerful binoculars spotted the Bird Dog from a distance, which proceeded towards the large flattop, slowly but surely. Lee flipped on the O-1’s landing lights, and banked into a small pattern above the ship, circling overhead. Chambers, up on the bridge of the Midway in the captain’s chair, was understandably extremely confused but also on the edge of his seat, trying to figure out if the small aircraft meant the Midway and her crew harm, or otherwise. He ordered the communications center to hail the Bird Dog on all frequencies and channels, but their attempts were met with static and a lack of response. The confusion quickly lifted when Chambers and the other officers on the bridge realized that that the Cessna contained more than just the pilot; there were children and a woman aboard as well.

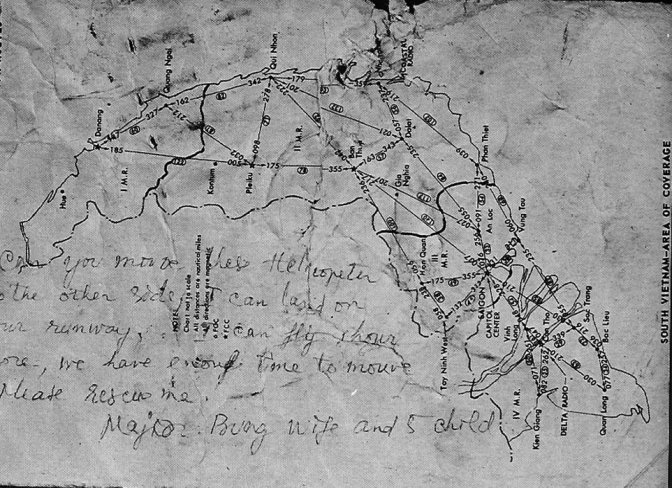

Unable to establish radio contact with the ship below him, Lee decided on a more rudimentary approach. Scribbling a note describing his situation on a piece of paper taken from the Bird Dog’s cockpit, he swooped in low over the flight deck and tossed it out of the window, hoping that someone would be able to catch it. This attempt, along with a second try failed as both notes blew over the side of the ship before the flight deck crew could get them. Now with less than an hour’s worth of fuel remaining in his tanks, Lee decided to add some weight to the third note, penned onto a map from the cockpit. Attaching it to his service pistol, he once again made a low pass over the carrier and dropped it out before climbing away. This time, the deck crew got a hold of it and immediately brought it to the carrier’s island, and then up to the bridge to Chambers.

Chambers called an impromptu meeting with the Midway’s Air Boss and the commanding officer of the Midway Carrier Task Force, Admiral William L. Harris. Outlining the situation that was unfolding right in front of their eyes, they quickly determined that the passengers of the Bird Dog had a very slim chance of survival if they ditched in the South China Sea, next to the carrier. Air Boss Vern Jumper and Harris concurred with Chambers that giving the Bird Dog a green light to land directly aboard the vessel would be the better alternative. Chambers did so and immediately put the ship’s crew into high gear. They had their work cut out for them.

During Frequent Wind and the gradual cessation of evacuation operations, the Midway had barely been making steerageway- just enough forward movement to helm the ship effectively. There was no real need for the ship to be moving any faster, as it was only supposed to be operating helicopters for the duration of Frequent Wind. Normally, it would have had to generate winds over the flight deck, so as to launch fixed-wing aircraft from its catapults, but helos didn’t need such a provision. Chambers had therefore allowed the ship’s engineering crew to partially shut down the powerplant for maintenance, upon their request. Now in need of speed to assist with Lee’s landing, Chambers got the Midway’s chief engineer on the line and asked that he be given enough steam to increase the ship’s speed to 25 knots. Due to the partial shutdown, this wouldn’t be possible right away, so Chambers had the engineering crew shift the hotel load (electricity used for every other purpose aboard the ship than propulsion) to the emergency diesel engines while cranking up the main powerplant. With that issue solved, another problem was manifesting itself outside on the deck.

Though Frequent Wind was coming to a close, helos were still flying to the ship. Chambers ordered all available hands to the flight deck, regardless of rank, to assist in moving any aircraft parked on the deck to a different spot, clearing a long strip for Lee to land on. Any helo that couldn’t be moved in a safe and timely manner was to be pushed over the side of the deck after a quick gear strip. An estimated $10 million worth of South Vietnamese UH-1Hs were thus stripped and jettisoned from the flight deck. When five more South Vietnamese Hueys landed on the deck during the mad dash to clear the deck, their occupants were hustled into the ship and their helos met the same fate as the others. Meanwhile, the arresting gear, strung across the angled deck of the Midway were also removed, lest Lee’slanding gear get fouled in the cables during his landing.

Keeping a keen eye on the deck, Lee brought his Bird Dog around and lined up with the ship, approaching just above stall speed. Chambers later recalled that Buang’s relative speed wasn’t more than 20 to 25 knots. As if he had practiced it a dozen times, Lee set the aircraft down on the flight deck and rapidly came to a halt amid the shouts and yells of the crew assembled on the deck to help facilitate the Bird Dog’s recovery. Many of the crew agreed- if Buang had a tailhook on his aircraft, he would have undoubtedly bagged the third wire (the the ideal wire for a textbook carrier landing). Shaking, but thoroughly relieved, Lee and his family emerged from the Bird Dog and were taken inside the ship’s island right away, where they met an equally-relieved Captain Chambers.

In the face of frightening odds, Lee’s story ended spectacularly well. The crew of the Midway unanimously donated money towards a fund that would help the Lee family settle in the United States after claiming refugee status, which they were able to, upon reaching the US. Captain Chambers’ actions could have very well had him court-martialled and killed off his career in the Navy, and he was well aware of that. Even still, he put his livelihood on the line and took the necessary actions to save the Lee family. Thankfully, Chambers was able to retire from the Navy later on after achieving flag rank and becoming a Rear Admiral. Years later, he would reunite with the Lee family, still ever grateful for Chambers and the Midway’s crew, and just what they did to save their lives on that overcast April day in 1975.

Amazing story. I’ve seen the photo of the helicopters being pushed overboard, but I always assumed it was so they ship could accommodate more people rather than to land a Cessna on the deck. Ironic that the evacuation witnessed some of the most redeeming events in the entire war.

LikeLiked by 1 person

More here: http://www.midwaysailor.com/midway1970/frequentwind.html

LikeLike

Great story! The Captain should have been promoted on the spot!

LikeLike

Maj. Lee’s O-1 Birddog is currently on display in the National Museum of Naval Aviation in Pensacola, Florida.

LikeLike

I had the distinct honor to serve under Captain Chambers and forever remember his role both in his initiation as a shellback and saving those honored veterans!! God bless the Chambers👏👏👏👏👏👏

LikeLiked by 1 person

Why didn’t they make fly the heli during a while an let it land back after the Cessna instead of throwing it away ?

LikeLike

I’m coming here a year later after your question and I have the same question as you. I can only guess that perhaps they were afraid that the Birdog landing might not be so clean and may trash the landing area for any aircraft. Having someone in the air (perhaps low in fuel situation) was not a great idea if they couldn’t land back on deck. perhaps someone with more knowledge can answer this at some point.

LikeLike

I’d read that, at that point, the ship faced an acute heli-fuel shortage. Supposedly, many had empty gas tanks, or close to it. Stands to reason, in light of the evacuation.

LikeLike

I was piloting USAF C-130s that day at U-Tapao, Thailand…my crew and I witnessed seeing many of the S. Vietnamese aircraft that fled South Vietnam when the North overran the South

LikeLike

Two very brave men and thank GOD. Our young men could learn something about vourage, passion and caring for their fellow human brings grom these men.

LikeLike

I’d like to point out that a lot of our young men are currently attempting to do the exact same thing as was described above for the Afghani translators who served with the US Army even at tremendous risk to their lives. They have sponsored them for visas since their lives, and those of their families, are increasingly at risk back in Afghanistan because of their work with the US. Many of these Afghani and Iraqi translators saved US American soldier lives, and made it possible for the our soldiers to work with the local populations when this was critical.

Unfortunately, even as American soldiers are working hard to bring their translators they worked with, along with their families, to the US, they’re running into a lot of red tape back in the US, even though we’ve only filled a fraction of the visas that Congress allotted for Iraqis and Afghans who served with the US Army and other branches.

See: https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2018/09/10/afghan-translators-risked-lives-deserve-us-immigration-visas-column/1204853002/

LikeLike